Few musicians have shaped American roots music as profoundly, or as quietly, as Doc Watson. With a gentle voice, remarkable humility, and an unmistakable command of the guitar, Watson helped forge the path that connected old-time string traditions to the modern bluegrass movement. His playing sparked an entire generation of guitarists to see the instrument not merely as a rhythm provider, but as a lead voice capable of speed, clarity, and soul. Though he never sought fame, Doc Watson’s artistry became one of the most powerful forces in the story of American acoustic music.

Early Life and Musical Beginnings

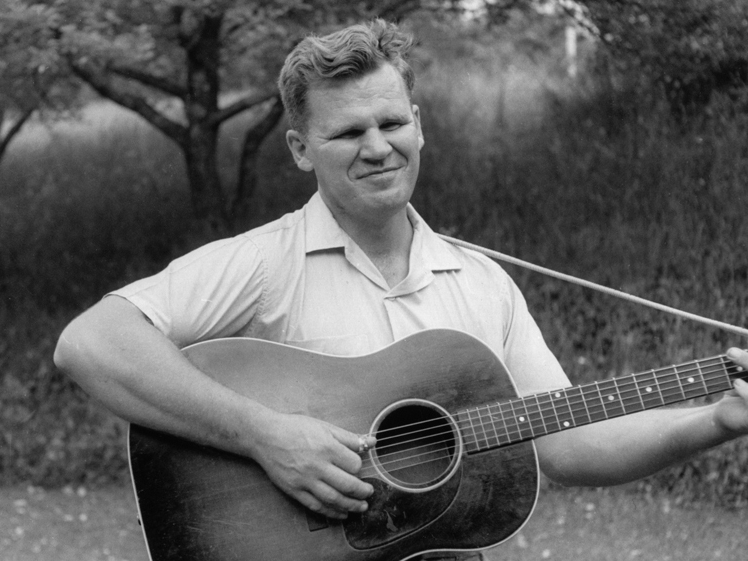

Arthel Lane “Doc” Watson was born in 1923 in the rolling foothills of Deep Gap, North Carolina. Blinded in early childhood by an eye infection, he grew up attuned to the sounds of the world around him: the cadence of mountain speech, the rhythm of hands working in fields, and most importantly, the music that drifted through Appalachian communities. His family was steeped in traditional songs, ballads, hymns, and fiddle tunes that had been carried across generations.

From his father, Doc learned the basics of the banjo, picking out melodies on a homemade instrument before he ever touched a guitar. Community square dances, porch jams, and the regional radio programs of the 1930s shaped his earliest musical sensibilities. When Doc finally picked up a guitar as a teenager—an instrument he purchased with money earned chopping wood—the direction of American acoustic music quietly shifted.

By his early twenties, Doc had already developed an assured, rhythmic style of guitar playing that allowed him to accompany fiddlers with unusual precision. He was hired for local dances and gatherings not only because he could keep the beat, but because he lifted the music with a brightness few guitarists could match. The seeds of flatpicking were already present, even before anyone had a name for it.

Career Highlights and Collaborations

For many years, Watson performed regionally, playing electric guitar in a local dance band and old-time tunes with family and neighbors. His national breakthrough came somewhat unexpectedly in the early 1960s through the folk revival. Musicologist and collector Ralph Rinzler heard Watson performing in North Carolina and recognized both the authenticity of his repertoire and the extraordinary skill of his playing. Rinzler invited Doc to perform at northern folk festivals, where audiences were stunned by his fluidity, tone, and sheer musicality.

Doc’s first major appearance at the Newport Folk Festival in 1963 launched his career. His performances were a revelation: a man from the Appalachian hills, playing centuries-old tunes with virtuosity that seemed effortless. His early albums, especially Doc Watson (1964) and Southbound (1966), showcased a musician who could move seamlessly from old-time fiddle tunes to blues, gospel, and ballads.

In the following decades, Doc performed with some of the greatest names in roots music, including Bill Monroe, Earl Scruggs, Chet Atkins, Merle Travis, Clarence White, and his son, Merle Watson. The father-son duo became especially beloved, touring extensively and recording a series of influential albums known for their warmth and tight musical interplay. Their partnership brought Doc’s music to an even broader audience, bridging the gap between folk, bluegrass, and country listeners.

Musical Style and Innovations

Doc Watson’s most enduring contribution to bluegrass and American roots music is his role in elevating flatpicking guitar to a lead instrument. Before Watson, the guitar was largely viewed as a rhythm tool within string bands. Fiddle tunes were for fiddles; breaks were for mandolins and banjos. Doc broke this convention with quiet confidence.

He developed a crisp, articulate flatpicking style built on old-time melodies, the drive of bluegrass, and the phrasing of thumb-picking guitarists he admired. His ability to translate fast fiddle tunes—such as “Black Mountain Rag,” “Beaumont Rag,” and “Salt Creek”—onto the guitar was nothing short of revolutionary.

What set Doc apart was not just speed or accuracy, but musicality. Every note had intention. His tone was round, warm, and relaxed, even at blistering tempos. He played with a sense of storytelling—phrases rising and falling like spoken language. Combined with his rich baritone voice and encyclopedic memory for traditional songs, Doc’s performances felt both effortless and profound.

Influence on Bluegrass and American Roots Music

While Watson did not consider himself strictly a bluegrass musician, his influence on the genre is immeasurable. His flatpicking style became the foundation for generations of bluegrass guitarists, including Clarence White, Tony Rice, Norman Blake, Bryan Sutton, and countless others who reshaped modern acoustic guitar music.

Watson’s repertoire also helped expand bluegrass beyond its early boundaries. By drawing from centuries-old British ballads, African American blues, shape-note hymns, and Appalachian fiddle tunes, he embodied the deep roots that fed the bluegrass tradition. His performances reminded audiences—and fellow musicians—that bluegrass was not isolated, but part of a living continuum of American folk music.

Perhaps just as important was Doc’s presence as a cultural ambassador. He carried the voice of rural Appalachia into urban coffeehouses, major festivals, and concert halls, offering a window into the traditions that formed the backbone of American acoustic music. His honesty, humility, and devotion to the craft made him one of the most beloved figures in the genre.

Later Years and Legacy

Tragedy struck the Watson family in 1985 when Doc’s son and musical partner, Merle, died in a tractor accident. Grief-stricken, Doc considered ending his career, but ultimately continued performing, often surrounded by musicians who helped carry forward the warmth and spirit of the Watson family sound.

In Merle’s honor, Doc helped create MerleFest, one of the most influential acoustic music festivals in the United States. Held annually in Wilkesboro, North Carolina, the festival reflects Doc’s musical philosophy: diverse, grounded, joyful, and community-oriented.

Throughout his later years, Watson continued to perform with grace and brilliance, even as age diminished his energy. Awards followed—multiple Grammys, a National Medal of Arts, and a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. Yet Doc remained unchanged at his core: a humble man who loved songs, loved people, and believed deeply in the power of music to connect hearts.

Doc Watson passed away in 2012, leaving behind a legacy woven into the fabric of bluegrass, folk, and Americana. His influence lives on not just in recordings, but in the playing of every guitarist who picks up a flatpick and tries to make melody sing.

Conclusion

Doc Watson stands as one of the most important figures in the history of American acoustic music. His contributions reshaped the guitar’s role in bluegrass, revitalized traditional Appalachian repertoire, and inspired generations of musicians to explore the depth and beauty of roots music. Through his impeccable playing, warm voice, and unwavering humility, Doc helped bridge the old and the new, ensuring that centuries of musical heritage would find fresh life in the modern world.

His legacy is not simply one of technical brilliance, but of connection—between past and present, between performer and listener, and between the countless musicians who continue to follow in his footsteps. In every tune played with clarity, heart, and respect for tradition, Doc Watson’s influence can still be heard.

Leave a comment