In the years when bluegrass was still carving out its identity beyond its Appalachian birthplace, it wasn’t only the biggest names who carried the music forward. The sound spread because working bands played relentlessly—clubs, radio spots, regional circuits—night after night, town after town, building audiences one handshake at a time.

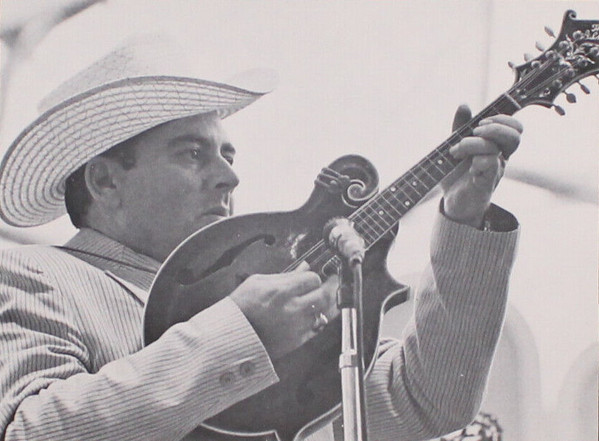

Among those bandleaders was Earl Taylor: a powerful bluegrass singer and mandolin player best known for leading Earl Taylor and the Stoney Mountain Boys. Taylor’s story is rooted in the places where bluegrass gained real traction in the 1950s—especially Baltimore, Maryland—and later in the Cincinnati, Ohio region, where he continued to perform and record.

Early Life and Musical Beginnings

Earl Taylor was born June 17, 1929, in Rose Hill, Virginia, a corner of the mountains where older songs, church harmony, and stringband sounds shaped the way musicians learned to play.

He was drawn early to the sound of the Monroe Brothers, and as his musicianship grew, mandolin became his signature instrument.

In 1946, Taylor moved to Michigan, played with a group called the Mountaineers, and soon formed an early version of what would become his best-known band name: the Stoney Mountain Boys. By 1948, he had disbanded the group and returned to Virginia—one of several turning points in a career that would keep shifting between regions, scenes, and opportunities.

Career Highlights and Collaborations

By the 1950s, Taylor was moving deeper into the northern bluegrass circuit—a world of clubs, small stages, and regional followings that were hungry for high-energy traditional music.

A major step came in 1955, when Taylor joined Jimmy Martin in Detroit and recorded with him for Decca. Not long after, Taylor returned to Maryland and in 1957 formed another version of the Stoney Mountain Boys, becoming closely associated with Baltimore’s bluegrass scene.

The Stoney Mountain Boys built a reputation in the places where bluegrass was becoming more than a rural tradition—it was becoming a true working-class, urban, weekend-and-weeknight music with loyal crowds who wanted speed, drive, and harmony you could feel in your chest.

The Carnegie Hall Moment (April 1959)

One of the most striking milestones connected to Earl Taylor and the Stoney Mountain Boys came in April 1959, when they performed at Carnegie Hall as part of Folksong ’59, a major concert event organized by folklorist Alan Lomax.

For bluegrass, it was one of those moments that carried symbolic weight—a music born in small communities stepping onto one of America’s most famous stages. It was the kind of appearance that said, plainly and loudly: this music belongs in the story.

Cincinnati Years, Recordings, and Continued Work

After that period, Taylor relocated to the Cincinnati area, where he kept the music moving through performances and radio and television work.

His recording legacy includes a well-known Capitol release, Blue Grass Taylor-Made, issued with his band the Blue Grass Mountaineers. Even as the bluegrass world changed around him, Taylor remained anchored in a traditional, hard-driving approach—built for bands that worked, traveled, and played to win the room.

Musical Style and Band Identity

Earl Taylor’s sound lived in the same world bluegrass fans cherish: tight rhythm, quick tempos, and vocals that sounded like they came from real life rather than polish.

Listeners and musicians remember the Stoney Mountain Boys for the kind of intensity that doesn’t need a spotlight to feel big—just a band that locks in, pushes forward, and means every note.

Later Years and Legacy

Earl Taylor passed away on January 28, 1984.

Today, his name carries the kind of respect that often belongs to musicians who didn’t chase mythology—they chased the next show, the next radio spot, the next town where bluegrass could take root. Earl Taylor and the Stoney Mountain Boys remain part of that essential story: how bluegrass traveled, grew, and proved itself far beyond where it began.

Conclusion

Earl Taylor stands as a vivid example of bluegrass at full working strength—a bandleader and mandolin player whose career ran through the clubs and circuits that truly built the genre’s footprint. From the Baltimore scene to the Cincinnati years, from regional stages to that remarkable Carnegie Hall appearance, Taylor helped carry bluegrass into new rooms and new listeners.

And in bluegrass, that kind of legacy matters: not because it’s loud in history books, but because you can still hear it in the way the music drives forward—honest, relentless, and alive.

Leave a comment