In the long story of bluegrass, history often shines its brightest light on innovators who arrive like lightning—transformative, unmistakable, impossible to ignore. But just as essential are the musicians who stay, who hold the line, who prove that a new language can be spoken fluently by more than one voice. Rudy Lyle was one of those musicians.

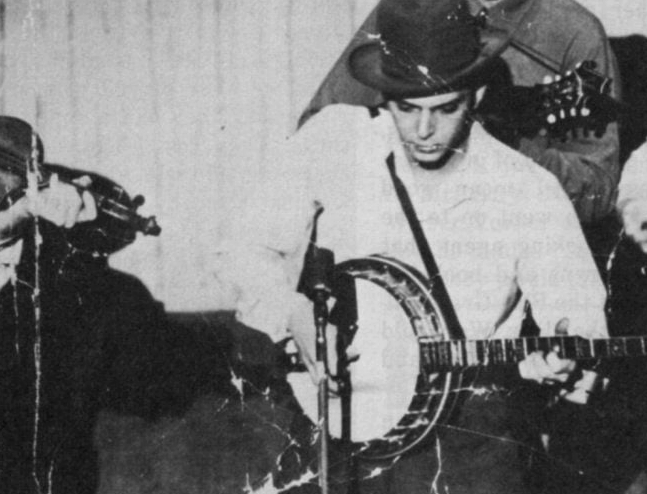

A gifted banjoist with deep musical sensitivity, Lyle spent years at the heart of bluegrass’s most demanding proving ground: Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys. He didn’t redefine the banjo the way Earl Scruggs did—but he confirmed, refined, and sustained it. In doing so, Rudy Lyle helped ensure that bluegrass was not a moment, but a tradition.

Early Life and Musical Beginnings

Rudy Lyle was born on March 17, 1930, in Virginia a region where string music was woven into daily life. Like many musicians of his generation, he grew up absorbing country, gospel, and old-time sounds from radio, family gatherings, and local musicians. By his teens, the banjo had become his primary voice.

The emergence of three-finger banjo playing in the late 1940s changed everything. Earl Scruggs had revolutionized the instrument, and for young banjo players, the challenge was no longer whether to adopt the style—but whether they could truly master it. Rudy Lyle was among the first who did. His playing was clean, rhythmically grounded, and musical rather than flashy. Even early on, he understood that bluegrass banjo was not about speed alone, but about timing, tone, and how the instrument fit inside a band.

Joining Bill Monroe and the Blue Grass Boys

In 1954, Rudy Lyle joined Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys, stepping into one of the most demanding roles in American roots music. Monroe’s band was famously unforgiving: musicians were expected to perform at the highest level night after night, often under intense pressure, with little tolerance for inconsistency. Many talented players passed through briefly. Very few stayed.

Lyle stayed.

Over the next decade and a half, Rudy Lyle became Monroe’s longest-serving banjo player after Scruggs, anchoring the Blue Grass Boys through constant personnel changes and an evolving musical landscape. His tenure coincided with a crucial period in bluegrass history, when the genre was solidifying its identity beyond its explosive beginnings.

What Lyle brought to Monroe’s band was stability. His banjo playing was precise and reliable, locking tightly with bass and guitar while leaving space for fiddle and mandolin to cut through. He didn’t compete with Monroe’s mandolin; he supported it. In a band led by a strong-willed visionary, that kind of musical humility was not only rare—it was essential.

Musical Style and Contributions

Rudy Lyle’s banjo style was rooted firmly in the Scruggs tradition, but it was never imitative. Where Scruggs often drove the band from the front, Lyle worked from the center, reinforcing rhythm and structure. His rolls were even, his accents tasteful, and his sense of timing impeccable.

He was especially respected for his backup playing—an art form often overlooked by listeners but deeply valued by musicians. Lyle knew when to step forward for a solo and when to pull back, letting the song breathe. His playing enhanced Monroe’s compositions without drawing attention away from them, a skill that requires both confidence and restraint.

Importantly, Lyle proved something vital to the future of bluegrass: the Scruggs style was not a one-man phenomenon. By playing it convincingly and consistently in Monroe’s band for many years, Lyle helped establish three-finger banjo as a standard language of bluegrass, not a passing innovation tied to a single personality.

Influence on Bluegrass and the Next Generation

Rudy Lyle’s influence is subtle but profound. While he didn’t become a household name, his work shaped the expectations of what bluegrass banjo should sound like in a traditional setting. For younger musicians watching Monroe’s band in the late 1950s and 1960s, Lyle was proof that excellence on the banjo wasn’t about reinventing the wheel—it was about serving the music with consistency and taste.

Many second-generation banjo players absorbed his approach, whether consciously or not. His style reinforced the idea that bluegrass thrives on ensemble cohesion, not individual dominance. In that sense, Lyle was as much a teacher as a performer, even if he never wore the title.

Within the Blue Grass Boys, his presence also allowed Monroe to continue experimenting with singers, fiddlers, and guitarists, knowing the banjo chair was secure. That reliability helped the band remain a living, working institution rather than a nostalgic relic.

Later Years and Legacy

Rudy Lyle remained associated with Bill Monroe longer than nearly any other banjo player, a testament to both his musicianship and his professionalism. In an era when many musicians moved frequently between bands, Lyle’s loyalty stood out.

His life was cut tragically short when he passed away on January 28, 1981, at the age of 48. Though his name may not appear as often in popular histories of bluegrass, his recordings and performances continue to speak for him—quietly, steadily, and with authority.

Today, among banjo players who study the lineage of the instrument, Rudy Lyle is remembered with deep respect. He represents the musicians who carry innovations forward and make them permanent.

Conclusion

Rudy Lyle may never have been the loudest voice in bluegrass, but he was one of its most important. By holding the banjo chair in Bill Monroe’s band for so many formative years, he helped turn a revolutionary idea into a lasting tradition. His playing demonstrated that bluegrass does not survive on brilliance alone—it survives on dedication, discipline, and musicians who understand the power of serving the song.

In the foundation of bluegrass, Rudy Lyle is a load-bearing beam. You may not always see him at first glance—but without him, the structure would not stand as strong.

Leave a comment